Long before the rise of annual grain based industrial agriculture, and the dismantling of our food and cultural traditions, humans lived in ways much closer to the earth. In some places hunting and gathering remained a viable option (even up to the present day), and in other places this relationship with the earth manifested itself through horticulture and various forms of animal husbandry. In many places it was a mix of these two ways of procuring food that shaped and defined a culture and/or a region.

For untold millennia (until relatively recently), humans had been able to provide for their basic needs through a combination of these two actions: Hunting/Fishing/Shepherding/Husbanding and the cultivation/gathering of plants for all of their dietary needs. These ways of life are not mutually exclusive, but rather a complementary set of skills and traditions that have formed the long and diverse history of humans, the food we eat, and how we inhabit, impact, and transform our landscapes.

The transition from hunter/gatherers to industrial agricultural farmers did not happen overnight. It has been a long drawn out story that has seen countless empires and kingdoms rise and fall, climate and weather patterns change, landscapes transformed, and cultural practices (some good, and some bad) that have led up to the present day. The part of this story that really interests me, and what this essay is going to explore, are some of the horticultural practices that came between the gulf of the hunting and gathering lifestyle and the transition to the industrial agricultural paradigm, and how the ultimate survival of the human species rests in reconnecting with these horticultural traditions.

For the last ten thousand years humans have undergone a transformation that has slowly eroded our abilities to be self reliant as communities. Year by year, and season by season unseen and unnoticed by most of those living through these changes, we have become more dependent on others to grow, raise, and process our food for us. But even as this has occurred, and continues to happen to this day, there are examples of resistance to the transition of mass produced food that is based on annual grain agriculture.

The kitchen garden, which in many regards is the original resistor to monocrop agriculture, is the heart of any homestead. They provide us with an abundance of fruits and vegetables, culinary and medicinal herbs, flowers, forage, liquid gold from honey bees, fodder for livestock and pollinators, beauty, a sense of well being, and a bit of self reliance. The kitchen garden, whether it is covering thousands of square feet as part of a rural homestead, or is an intensively managed set of raised beds in an urban neighborhood, has traditionally provided us with a majority of our essential vitamins, nutrients, and minerals that we need each day to remain healthy.

The kitchen garden has been the difference of merely surviving on a subsistence diet of staple grains or other forms of cheap industrial grown carbs, and thriving because of a diet consisting of healthy leafy greens, fruits, berries, legumes, stems, nuts, tubers, roots, and different forms of animal protein. It is the kitchen gardens, allotments, community gardens, urban farms, and small scale polycultural farms found throughout the world and its history that have helped to feed the civilian population in times of war and peace, economic prosperity and downturns, and periods of climate change and stability.

As far back as ancient Rome, before it was an empire dominated by politicians and imperial armies, citizen farmers worked the land as families. Their farms were small, diverse operations worked by hand that provided all the food a family needed to survive. David R. Montgomery, the author of Dirt – The Erosion of Civilisations, sums up early Roman horticultural practices in this passage –

“Early Roman farms were intensively worked operations where diversified fields were hoed and weeded manually and carefully manured. The earliest Roman farmers planted a multistory canopy of olives, grapes, cereals, and fodder crops referred to as cultura promiscua. Interplanting of understory and overstory crops smothered weeds, saved labor, and prevented erosion by shielding the ground all year. Roots of each crop reached to different depths and did not compete with each other. Instead, the multicrop system raised soil temperatures and extended the growing season. In the early republic, a Roman family could feed itself working the typical plot of land by hand. (And such labor – intensive farming is best practiced on a small scale.) Using an ox and plow saved labor but required twice as much land to feed a family. As plowing became standard practice, the demand for land increased faster than the population.”

Farmers from ancient Rome.

This passage highlights a few points that are well worth looking at in more detail. First, the description of the crops grown illustrates the importance of genetic diversity. While the Romans did not have the word Permaculture, the fact that their horticultural choices included tree crops, vines, ground covers and annuals shows that they understood the importance of genetic variation within their farmsteads. Genetic diversity within a particular crop selection almost always insures a harvest of some kind, and by designing this resilient feature into our farms, we can avoid complete famine in a bad year.

Second, these early Roman farmers knew the importance of a healthy, living soil even if the finer details of microorganisms and soil life were not fully understood. By returning manure and organic matter back to the fields, and growing a diverse selection of perennial food crops (along with some annuals), the soil health was maintained and continually improved upon. But gradually throughout the empire the Roman family farm began to be replaced with annual grain production that depended on the tilling and plowing of the fields to support an elite urban empire. Once this occurred the resilience of these small horticultural farms was lost to the history books.

At this point in Roman history, absentee land ownership took over, soil was lost to water and wind erosion, and farm labor moved in the direction of slavery. These are all signs, still seen today to some extent, of what happens when our horticultural traditions are replaced with annual monocrop grain production to feed the cities. This transition does not happen overnight, and is almost invisible to those living through it. Only in hindsight and with an accurate historical narrative can we see the effects of what annual mono-crop based agriculture does to a once thriving, self reliant culture.

Moving on to another example of a multi species, horticultural society, we find ourselves in pre-industrial China. While China has suffered many famines, environmental degradations, and massive amounts of soil loss due to poor farming practices and land stewardship, not everything in this ancient culture’s history is doom and gloom. Focusing solely on southern China, there is a roughly 10,000 year old agricultural tradition of growing rice along with fish and ducks.

This farmer is carrying on a tradition that is millenia old.

This polyculture of rice, fish, and ducks provided a substantial part of southern China’s diet on land that was marginal at best. Through intensive land management of irrigation ditches and rice paddies, and the continual addition of human and animal manures to these areas, the pre-industrial Chinese farmers were able to work these same lands for millennia without degrading the soil. This technique of multi-species farming was so successful that the population would balloon in times of prosperity and occasionally overshoot the carrying capacity of the landbase, leading to isolated periods of collapse, famine, and death.

In addition to the rice, fish, and ducks, Chinese farmers also raised chickens and pigs, and cultivated amaranth, asian beans, barley, brassicas, leeks, melons, millet, turnips, and many other old world annual vegetables that added richness to their cuisine and health. Fungi and herbs that have traditionally been used in Chinese medicine have now gained notoriety throughout the world, and as far as perennial contributions from their horticultural traditions, apricots, apples, bamboo shoots, citrus, lotus roots, and peaches also played large roles in feeding the pre-industrial farmers of China.

Like the example of the Romans, as ancient China grew and added more and more urban areas, the population increased and demanded more from the land. As this happens, shortcuts are taken and eventually people start to change the way they grow their food. Demand dictates efficiencies, so rather than keeping age old methods of growing and raising food for small communities using proven sustainable methods, new ways are invented to grow and export more food to the ever growing urban areas. As this happens land stewardship ceases to matter, and as a consequence soil is lost, and civilizations fail.

An example of genetic diversity within the indiginous crop of the Andes mountains – potatoes!

Moving along to one last pre-industrial horticultural society, we find ourselves across the two great oceans in pre-European North, Central, and South America. While this land mass is huge and contained many diverse cultures, there was a shared, underlying similarity displayed by many of these first nations of the Americas. While it is true that the Americas’ had its own agricultural revolutions with crops like maize and potatoes (and flourishing kingdoms and urban centers that were supported by these crops), the pre European Americas were highly managed landscapes overflowing with an abundance of useful plants and animals despite what the first Europeans thought was an untouched, virgin wilderness.

One major difference that set the Americas apart from Europe and Asia is that there were no domesticated animals aside from the dog that were a part of their horticultural systems. While it could be argued that the guinea pig and possibly the turkey were partially domesticated, there were no beasts of burden prior to the arrival of the Europeans (and the animals they brought with them) that aided in the transformation of the landscape, thus giving it its wild appearance.

This fact alone sets the stage for the reasons that the original inhabitants of the Americas managed the land the way they did. With no domesticated animals to keep track of or feed, there were no fences or pastures in the landscape. Therefore all meat and animal products were procured from undomesticated sources. The work of clearing fields was done first with semi controlled fires, and then using wood and bone hand tools to finish removing charred stumps and other debris, fields were then planted in any number of indigenous crops. The same way manure adds nutrients and minerals to the soil, so too does fire from the (semi)annual burnings.

Fire not only cleared out fields where they grew the Three Sisters (maize, beans, and squash – Roughly Mexico north through Minnesota ), potatoes in the central and southern American highlands, and manioc root in the tropics, but fire was also used to keep undergrowth in the forests (continents wide) from getting out of control. The great savannas in the Eastern and Central United States, described by Lewis and Clark in their journals that contained American Chestnuts, oaks, maples, and many other trees were not wild tracts of land, but highly managed food forests that provided a variety of nuts, fruits, greens, medicinal herbs, and meat protein from the animals that also called these forests home.

Variations on this theme of the food forest could be found throughout the Americas. From the northern climes all the way down to the tropics and beyond; each region had its own diverse set of species that flourished with the help of the native populations and the fire they used to shape the land. Even the tropics and the great Amazonian rainforests are now thought to have been food forests and gardens that were managed by the local populations whose numbers are now believed to have been much larger than first thought. The evidence of terra preta, a mixture of charcoal, fired clay, manure, and other organic matter that is highly fertile that is found throughout huge swaths of Amazonian soil, is now thought to be evidence of a very hands on approach to the management of land that was once considered to be virgin wilderness.

With the arrival of the Europeans to the Americas, the world changed forever. Disease spread like wildfire and decimated native and imperial populations alike (this included non human species as well). Plants and animals from all corners of the globe began their international migrations. Maize, potatoes, and tomatoes from the Americas, wheat and barley from Europe and the Middle East, and apples, citrus, melons, and rice from Asia all became global crops. Honey bees, horses, cows, chickens, and pigs all became global animals and farming practices around the globe began to radically change, which in turn affected how communities prospered or failed, and how landscapes were altered. So while it can be said that monocrop grain agriculture started well over 10,000 years ago, it was with the advent of the Columbian exchange that it took on a new global approach that has altered our planet radically.

Today our kitchen gardens and small scale farms are made up of global plant immigrants. Whether you are in Africa, America, or Australia, the joy of a garden fresh cucumber, tomato, or onion is now a shared experience. And while the globalization of plants and animals has had downsides such as the spread of pests, disease, and “invasive” species, it has also provided us with many new opportunities to help feed ourselves and heal the land after so much abuse and mismanagement at the hands of modern civilization and the agriculture that has made it possible.

Having this plethora of plants (and animals) at hand to work with can now be considered an asset and another tool for us to use as we adapt to our new living arrangements. As Bill Mckibben has so eloquently wrote about (see his book Eaarth), we no longer live on the planet that we grew up on. The realities of climate change are real, and when combined with peak oil, habitat loss, and nuclear contamination humans have been backed into a corner that will be hard to get out of alive.

The horticultural traditions from the global past may now be our best shot for the survival of the human race along with all the good parts of our collective culture – i.e. – music, art, poetry, community, family, etc. When we can all become producers again, rather than just blindly consuming, we begin to occupy one of our historical roles as land stewards. Since so few of us have any connection with the Earth anymore, we no longer know what it needs or how to care for it. When we no longer live with the Earth, we no longer know its rhythms and fall out of balance with our evolutionary roles as caretakers. Every year more soil is lost to erosion, aquifers are drained and contaminated, wild habitat is plowed under for field crops and development, and human culture moves further away from our evolutionary roots. This has been our fate, but now is the time to free ourselves from the shackles of civilization and move onto the next stage of evolution.

Our shared horticultural traditions, whether that be from the terraced slopes of China to the food forests of pre-Columbian America are examples of what is possible. While we may never be able to recreate some of these systems as they once were, the lessons they have to teach us are timeless and offer real solutions for our journey into the future. The ecological design science of Permaculture gives us an opportunity to take all of these diverse traditions and blend them into a new, adaptable way for us to inhabit the Earth. As we begin this journey, we will see that modern, industrial grain based agriculture is incompatible will our ultimate survival on this planet. Only when we begin to think long term and include future generations into our plans will we be able to affect real, positive change.

So while planting biodiverse gardens with fruit and nut trees in and of itself is not the answer to all of the problems we face, it is a big part of the solution. The challenges we are up against are compounded by so many factors, but food is one of the underlying commonalities that ties everything together. When we begin to rethink how we grow our food and look to the past for examples, that is when we can truly move forward and begin the healing process of ourselves and our one planet. I leave you with one final thought, a favorite quote of mine that sums up our journey thus far. “Societies grow great when old men plant trees whose shade they know they will never sit in.” It is not too late for us, lets do something epic and grow old together as one human culture! Peace and Cheers

Read Full Post »

Fruit tree cultivation has been a part of human history for thousands of years. Since before records, farmers and gardeners across the globe have traditionally incorporated fruit trees into their landscapes.

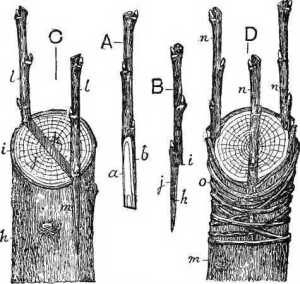

Fruit tree cultivation has been a part of human history for thousands of years. Since before records, farmers and gardeners across the globe have traditionally incorporated fruit trees into their landscapes. The cleft graft is a great place to start grafting due to its simplicity. All it requires is a centered, vertical slice down the rootstock (creating a cleft), and making two identical cuts on either side of the scion wood basically turning it into a slim wedge. The scion is then inserted and slid down into the cleft of the stock, all the while keeping the cambium layers lined up. The cleft graft allows you to use smaller scion wood with a bigger diameter stock. Once you are happy with the alignment of the cambium layers, wrap your graft with grafting tape or a binder, and then coat with wax or parafilm to help prevent desiccation.

The cleft graft is a great place to start grafting due to its simplicity. All it requires is a centered, vertical slice down the rootstock (creating a cleft), and making two identical cuts on either side of the scion wood basically turning it into a slim wedge. The scion is then inserted and slid down into the cleft of the stock, all the while keeping the cambium layers lined up. The cleft graft allows you to use smaller scion wood with a bigger diameter stock. Once you are happy with the alignment of the cambium layers, wrap your graft with grafting tape or a binder, and then coat with wax or parafilm to help prevent desiccation. The whip and tongue graft is a bit more difficult than the the cleft graft, but with a bit of practice becomes quite easy. The whip and tongue is prefered when the scion wood and your grafting stock are of almost similar diameters. It allows you to maximize cambium layer contact, and makes for a stronger graft union. Both the scion wood and the stock get a long diagonal cut that when put together, line up and form a new single branch or tree. The secret to a good whip and tongue graft is the second cut you do on each piece which creates the “tongue”. This tongue allows the two pieces to lock together, and because of the natural elasticity of the wood, this does a great job in helping the graft union to heal very strongly.

The whip and tongue graft is a bit more difficult than the the cleft graft, but with a bit of practice becomes quite easy. The whip and tongue is prefered when the scion wood and your grafting stock are of almost similar diameters. It allows you to maximize cambium layer contact, and makes for a stronger graft union. Both the scion wood and the stock get a long diagonal cut that when put together, line up and form a new single branch or tree. The secret to a good whip and tongue graft is the second cut you do on each piece which creates the “tongue”. This tongue allows the two pieces to lock together, and because of the natural elasticity of the wood, this does a great job in helping the graft union to heal very strongly.